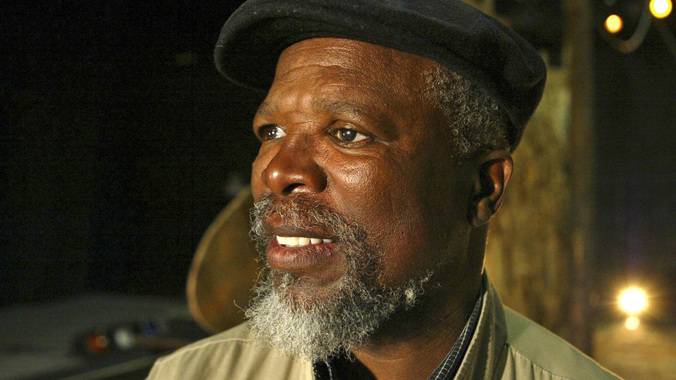

Renowned actor and playwright John Kani talks to Brent Meersman about his new play, “Missing”, now showing at the Baxter Theatre.

Well-known actor and playwright John Kani was booked off for a week during rehearsals due to a lower back injury that forced a postponement of the opening night of his new play, Missing. Otherwise, Kani, who turns 70 this year, appears in good form. He downplays the injury when I ask, and his face doesn’t once betray what must be a painful condition. He’d rather talk about the work – Missing – his first full-length play since his Nothing But the Truth in 2002, than ailments.

What made you write Missing?

From the [19]70s, whenever you spoke to the exiles they were thinking about: “One day, we go home”. When they are reminiscing, you are nervous to tell them something is no longer there. What you do then is take away the pieces of memory, which they put together and call home. Anything you say is no longer there, leaves a huge blank in their memory bank which makes them unable to remember home, especially those who married the natives of lands of the countries that hosted them. Robert [the main role, Kani will play on stage] is one of those. He married a young girl from Stockholm – Anna. Everything is fine. They have children, jobs, his wife inherits a billion-dollar business, his daughter is a medical intern, and she is already engaged to Carl. But as a Xhosa tribesman, he wishes it was a Sipho. In his heart, he wishes to go home and have a traditional wedding.

Now, on February 11 1990, a miracle happens. They watch their lives, their history, their background unfold as Nelson Mandela walks out of prison.

Do we see this on stage?

No, it has happened already. This is when this family is rocked. Daddy [Robert] saying I am going home is becoming a reality now. Daddy lived in New Brighton, a small three-roomed house where he was born. He’s been in Stockholm for over 30 years, but home for him is that house. Imagine now marrying a daughter of a billionaire and you now want to go back home to that little house. It’s uprooting an entire family.

Now put that together with the first group of comrades. In his mind, his name is on the list of people to fly back to be part of the [democratic] negotiations. But when his name is not there, it hurts him to a point of not even being able to look at the family. It seems they’re charging him, asking him, why aren’t you called? What have you done wrong?

I remember being detained [under apartheid] and the police leave you for a day without telling you anything. You run through your life in detail, backwards; who did I meet? Who did I say that to? When you’ve gone through all the friends and acquaintances, you go to family. Did my brother talk too much? It is a self-torture.

Now in 1999, Thabo Mbeki becomes president, hope flickers again. But [again] his name is not on the list. The family say they can’t take it. This is not a family – him sitting there, waiting for the president to call. That’s where the play starts.

The family says, go home, go see the president, ask him why. Maybe when you get the answer you will no longer be missing in action.

Is it a companion piece to Nothing But The Truth, in the sense that you told the story of return from those left behind. Now you are telling the story from the point of view of the returnees.

No, but there is a DNA thread … You right, he [Robert in Missing like Sipho in Nothing But the Truth] is also looking at his age, his daughter is going to get married, there is a custom we need to do as Xhosas … Mrs Thabo Mbeki, after seeing the play [Nothing But the Truth], said to me: “John, not all of us were like Themba in exile. Some of us struggled and suffered, especially us women who stayed in these one-roomed flats, never with your husband. I’d love to tell you that story one day” … You see, I made Themba this flamboyant bullshit politician. Those were the goggas that started to have a conversation with me when I was formulating the story.

So did what happen to Robert happen to people in exile?

I remember asking Thabo Mbeki, a good friend of mine, is it possible there is someone out there you missed? Someone you didn’t call? And he just said: “John, it is possible.” He left it there.

When I was in London doing The Tempest, I asked our high commissioner the same question, and she said, yes, there were many. You see the committee to arrange the return was a committee of human beings, with human flaws. If one person on that committee didn’t like you … And it became about positioning for jobs. Those were the little internal conflicts and politics. These are the things we didn’t know about, then. This excited me to write the story

What do you think of the state of playwriting now in South Africa, and how does it relate to your plays?

We grew from a culture of novelists and short story writers. When it came to drama, we had an unknown genre called workshopping, which was very useful. We performed Sizwe Banzi for three years without a text [to circumvent apartheid censorship laws].

The challenge came when Mandela was released. We are now also part of the problem, not just the solution. We no longer have an enemy to which our work is directed. We were all faced with a blank page. We had to go back to African story-telling, folklore and folk tales … You always feel [when writing] if I could just get the actors in the room I could do this in [minutes].

We are developing, but people are still crazy about doing other people’s plays and the classics. Now we are part of the world. South Africa is hungry for the massive spectacle of production [the big musicals] … not the table and two chairs. Writing is slowly developing among us who are telling a story. You remind yourself: “I am post-1994. If I am writing about pre-1994, am I hogging the past? If I write post-1995, am I neglecting the past?”

So when I write, I focus on the story of a particular human being – Robert in Missing, Sipho in Nothing But the Truth. I’m putting Robert into a laboratory through various tests to see if he falls apart. I give him a wife who can’t go home, a daughter he loves but is Afro-Swedish, a friend he trusts who betrays him – all these things are the dynamics around the story, life and journey of Robert.

So this is the dynamic – the political conspiracy, intrigue and betrayal by his own comrades, and on the other hand, it is a family confronted with this new problem called going home. It gets to the most ugliest confrontation ever between the two [Robert and his wife]. It even touches on rich and white and black and all the ugly goggas that have never been considered by this intercultural marriage before.

Adelaide Tambo always said to the young wives of the political exiles: “Remember, you always share your husband with the struggle, and you must be prepared at times to be the second wife.” In the end, decisions and choices have to be made.

Does Robert return to Stockholm or stay on in South Africa?

I gave Zakes Mda the rough first draft. He said: “Robert mustn’t go back to Stockholm.” I took it to Janet Suzman; she said he must go back to Stockholm. (Kani chuckles) I gave it to Janice Honeyman to direct; she said on two conditions – one, you play Robert, and second let’s not decide now whether he goes back or not.

It seems to me harder than ever to put on a dramatic theatre work such as Missing these days. Why?

Pieter-Dirk Uys once said something – I really wanted to kill him for it. He said, if the Market Theatre ever gets funding, which it never did right up to 1994, then that will be the death of the Market’s creativeness. I got to so angry at him, but then I thought about it: in 1995 we get R6-million from the government. Our little bookkeeper all those years was now not enough. We needed a proper accountant, a [chartered accountant] who opened an office; we needed internal audits, external audits, approved auditors, finance and executive meetings. We spent the rest of our lives making sure we could account for this money and there was less creativity.

Number two, the government grant cannot be used to produce a play.

Thirdly, artistic directors are more and more nervous about breaking even. So we are now as writers asked to write hits. Because how is the artistic director going to motivate that this one [play] will make money?

Fourth, the restructuring of the theatres in this country … the head of the theatre is now a chief executive, answerable not to a board, but to councillors, and they have a fiduciary duty. It is them you must convince with a budget and 90% of these people have nothing to do with theatre. They are just known accountants, known lawyers, known people.

Number five, your theatre must be available to the community and yet we have no funds enabling that community to bring in the work … All these factors are juts crippling and paralysing the would-be writer. What’s the point of writing a play when there is an 80% likelihood it won’t happen? That’s’ why Zakes [Mda] says he writes novels. He says: “You are very lucky because Nothing But the Truth was prescribed as a matric setwork.

The quality of work has improved. South Africans are writing great plays. We do these community festivals as compliance, but there isn’t even someone working with these young people. They never graduate. They are locked into community theatre.

When will another John Kani come out of community theatre?

Fugard is still writing plays.

Every play he brings back, I hold my hand and think, I miss my friend. I miss the fire, the recklessness. I miss the dangerous Athol Fugard. I watched him directing [in the past few years] and think he would never have allow us to do that. He would rip into us, to the point you think: “I am going to kill that white man.” He now writes from memory, and memory and distance are the most dangerous things in an artist’s life. You have to write from the smell around you, the eye witnessing what your ears receive. But it’s writing [Fugard’s recent work] that is very important. And he is still telling stories. Maybe we are unfair to think those stories should be about South Africa. The time he has been overseas is too [long now], and it’s beginning to tell in his work.

You have been very successful. Haven’t prospects improved for black actors? I’m thinking how in the past the only roles were conductor, maid, baggage attendant, chauffeur, butler and so on. That was all the film industry offered. Now Atandwa [Kani’s actor son] has very different prospects.

After Mandela became president we were the most desired in plays, movies, on boards. If it didn’t have a black person it was not kosher, not democratic, not non-racial, not dealing with redress and diversity. (Kani chuckles) So we found ourselves sitting on boards being paid R3 000 for a meeting because we needed to be there.

The new generation, they have to be in it. And thank God some of them have the talent to stand the ground and make their mark.

Why were you so much more successful than Winston Ntshona [Kani’s acting partner for years and co-Tony award winner]?

In 1986, after my father died and my brother was shot in 1985, I said I have to get out of this small town. I feel I’m going to die here, my career or my [actual] life. Winston said he would stay and see what he could do [for theatre]. I took my step, I became a gypsy. I followed my nose. Winston worked on the youth and development when there was no funding. He worked, [developing] a cultural centre. But the Bhisho government, through corruption … the money disappeared. The place still stands there as a haunting apartheid burned-down bottle store, and with it died so many young people’s dreams.

Winston and I understand that life makes those decisions for [us]. The fact that it appears as if I am more successful does not mean artistically I’m more than him.

Missing runs until March 29 at the Baxter Theatre, Main Road, Rondebosch 7700, Cape Town.

Via Mail & Guardian