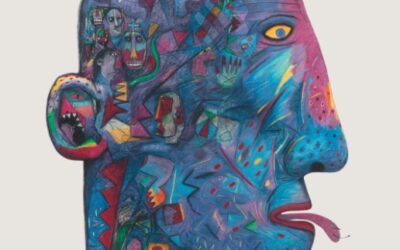

Photographer Pieter Hugo’s latest exhibition Kin, at Stevenson, is a ‘jolting meditation’ on family, kinship and decaying nationhood, writes Sean O’Toole.

Eight years ago, Cape Town photographer Pieter Hugo; who is concurrently showing his new exhibition Kin in Cape Town, Johannesburg and New York; visited the Gorongosa region of central Mozambique. There he met up with Piet van Zyl, a former soldier turned farmer and ecotourism entrepreneur, and photographed his son, Sakkie, in the Arcadian splendour of the southern Rift Valley.

At the time Hugo posed this barefoot adolescent waist-deep in lush grassland, he was known mostly for his studio portraits of the elderly, the blind and people with albinism. These inexpressive typological portraits, initiated while he was still working for Colors magazine in Italy, had, however, run their course.

Hugo began exploring new avenues – both formal and thematic; for his personal photography. One strand involved thinking about his Afrikaner identity.

“Being Afrikaans in this country at the moment is a very weird position to be in,” he told me in 2005. “There is this unspoken cold war against Afrikaners. You can’t go anywhere else, yet you’re African, but you’re not considered one.”

Rather than shrink from this situation, he confronted it head-on. In the same year he photographed Van Zyl, Hugo travelled to Durban to record a group of bare-chested minibus taxi washers. He also visited Ghana, where he photographed a group of impoverished honey collectors who use leaves and plastic bags as protective wear.

But it was his 2005 portrait series of a group of Hausa entertainers posed in dusty Harmattan landscapes with their hyenas, monkeys and snakes that gained him international attention.

For a brief while after one of his Nigerian photos won him first prize in the portraits section of the 2006 World Press Photo competition, Hugo continued to explore his white Afrikaner identity. In 2006, he photographed Francois and Le Roux Hoffman, two Makhado youths, in their suburban garden.

Before embarking on a protracted stint making new work elsewhere on the continent, memorably in Nollywood, Hugo also completed an essay on Musina, a ramshackle border town north of the Soutpansberg. Among the many subjects he corralled on to couches during 2006 were the Louw family: father Koos, mother Maureen and their two sons, Gustaf and Marco.

This portrait, which captures a moment of genuine warmth and unspoken love between the Louws, appeared in Hugo’s 2007 book and exhibition Messina/Musina. It now also forms part of Kin, his jolting meditation on family, kinship and decomposing nationhood.

Hugo has stark views on the state of the nation. “South Africa is such a fractured, schizophrenic, wounded and problematic place,” he offers in a statement accompanying Kin. “I have deeply mixed feelings about being here.”

Marriage and the birth of his two children have acutely sharpened his awareness of the difficult – historical, social, economic; context in which he is raising a family.

Hugo is transparent about this in his work. Kin includes numerous portraits of his immediate family, among them a 2009 portrait of his grandmother, Anna Hugo. His parents, Lize and Gideon Hugo, also agreed to be photographed in bed, at the family’s beach retreat at Gonnemanskraal on the West Coast. From this place of blood and intimacy, the circle of affinity incrementally widens.

Kin includes a study of Ann Sallies, the domestic worker who helped to raise Hugo. This graceful portrait possesses uncommon warmth; it shows Hugo capable of Vermeer.

Hugo’s pregnant wife, film editor Tamsyn Reynolds, is the subject of two portraits. One, a tightly framed three-quarter study on show in Johannesburg, is a noteworthy disquisition on motherhood and femininity. It is also, depending on the sort of probity you expect of husbands, fathers and artists, unkind. It is a way of seeing worth exploring —and defending.

But for the Louws, the only other smiling face in Kin is a wax mannequin likeness of the world’s first heart transplant recipient, Louis Washkansky. He lies on his back perpetually waving in the Heart of Cape Town Museum. The photograph reminds me of the cheery Mandela mannequin photographed by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin at Emperors Palace in 2004. In both, the smile has been manufactured for entertainment, nothing more.

If Kin marks the closure of a process of inquiry initiated in 2005, it also heralds a maturing eye. Hugo’s still lifes; in particular his “aerial view” of Sowetan Sipho Ntsibande’s cellophane-wrapped TV remote controls and box of cigs, as well as his study of decaying fruit and vegetables in the sullen interiors of a Germiston home – are remarkable.

Kin is possibly a diverting title for his project. Much of the exhibition comprises strangers, some smoking (like the quizzical Capetonian Shaun Oliver), others wearing strange wounds (like the prison tattoos on the face of Daniel Richards and burn marks on the body of Winston Niebuhr).

Perhaps rigtingbedonnerd, the hard-to-translate title of journalist Fred de Vries’s new book on the post-1990 white Afrikaner, would have been better. In a Litnet interview De Vries offers that pride, black humour, unwavering commitment, hospitality, love of the underdog and a tendency towards melancholy define the Afrikaner.

This melancholy is etched into Hugo’s flesh. Kin includes a 2010 self-portrait of Hugo, naked and tattooed, with his newborn daughter. “Et in Arcadia Ego” reads the curlicue quote, which is also the title of a famous pair of paintings by Nicolas Poussin. “Even in Arcadia, there am I.”

Art historian Erwin Panofsky described Poussin’s work, which depicts shepherds appraising a tomb, as part of the “elegiac tradition”. Elegy: it is also a fitting title for this mournful, probing, argumentative and, in its own way, devastating exhibition.

Kin is on at the Stevenson in Cape Town (Buchanan Building, 160 Sir Lowry Road , Woodstock) until November 23 and at the Stevenson in Johannesburg (62 Juta Street, Braamfontein) until November 8.

via Mail & Guardian.