The Malibu Model has reached Cape Town. And for those who want to get sober, and have the kind of cash that gets you the best, it’s a beautiful thing, reports Tanya Pampalone.

The Malibu Model comes with highly individualised treatment plans and extras such as acupuncture, equine therapy, yoga and meditation, a sumptuous departure from the clinical, bare bones, tough love approach that’s offered at many rehabs.

Tanya Pampalone takes you on an extensive journey through the many facilities available in Cape Town and ends with her meeting with Dr Roger Meyer. See the full report in the Mail & Guardian

Growth industries

“What are Malibu’s growth industries?” asked a recent New York Times article. “Answer: Winemaking and sobriety.” It’s a question that could be as relevant to Cape Town as it is to Malibu.

I thought I might begin my journey at Montrose Place where, in the early days of 2010, there was rampant speculation by both local and international media that Tiger Woods had checked in for sex addiction after his string of marital infidelities became public.

It was never proved that Woods even set foot in the country, much less the luxury treatment centre, which opened in 2007. But, out of it, a star rehab was born.

The next day I found myself in the genteel suburb of Kenilworth meeting Dr Roger Meyer at the psychiatric group practice which specialises in addiction medicine. Housed in a refined office with hardwood floors and dark leather couches, it exudes the particular, fragile quietness found only in rooms such as these.

The practice sits across from the Akeso-owned Kenilworth Clinic, the psychiatric hospital where Meyer began his foray into addiction medicine.

Severely damaged hands

Meyer, who wore comfortable jeans and a grey K-Way sweatshirt, his readers perched on top of his head, told me he worked as a GP through a harrowing intravenous drug addiction that left his hands severely damaged; they are thick, like baked bread, and if you look closely you will see the tiny pockmarks, which are scars from abscesses left from repeatedly injecting himself.

“My little works of art,” he says.

Meyer got clean in the United Kingdom more than 25 years ago. But upon his return to South Africa, he couldn’t find a Narcotics Anonymous meeting to support him in his recovery. So he started his own. (There are now more than 70 meetings you can attend on any given week in the Cape Town area.) He continued in private practice until he began to amass a patient roster that included an increasing number of addicts.

In 1992 he and Carrie Becker, who would handle the therapeutic part of the project, started up an addiction unit at Kenilworth Clinic, the first in the country. (They split, with some differences, in 1996 when Becker was offered the hotel in Kommetjie. Eventually Meyer acquired a share in the clinic, selling it later to his partner, who then sold it on to Akeso in 2012.) Since then, the number of private treatment centres has mushroomed. There are now more than 30 operating in the Cape Town area, 19 of those being in-patient clinics.

In his silver Mercedes, we took a tour of the addiction medicine saturated neighbourhood – Tharagay House, Meyer’s own treatment centre, the secondary facility Kenilworth House, as well as the Living House, a sober living home, are just a few – while he told me of his journey through addiction medicine.

“Nobody has spawned their own competition more successfully than I have,” Meyer told me. “They have either worked for me or been patients of mine, and I won’t say which. And I’m proud of that. If you look around the world, there are little focuses of addiction treatment expertise – southwestern England, the States, Australia. We’ve got a whole network of respected facilities.”

One of those is Seascape House, which Meyer opened in 2008.

Situated in Dolphin Beach, Bloubergstrand, from the outside it looks like a boutique hotel. I found the chef, who trained at Zevenwacht Wine Estate in Stellenbosch, in the kitchen, preparing rocket, avocado and feta salads for lunch.

The 12-person facility, which, when I was there had almost all foreign patients, charges R35 000 for locals with an extra 20% premium for foreigners. It has a unique setup.

Clients who come here have already detoxed and most stay for two months. After the first week, they have access to their cellphones and their computers; they can even go down to the corner café for a coffee, and hopefully not something more stimulating.

But, as Meyer says: “If you are going to relapse, the best place to do it is in treatment.”

Sadly, relapse is often part of the recovery process. But try telling that to an addict’s family member who has just shelled out tens of thousands of rands, only to find their loved one smoking or snorting or shooting up days, months, or even years later.

“It’s not like having your appendix out, where you go in a hospital with a sore tummy, your appendix is removed and you leave three days later and you are more or less cured. Addiction is a chronic problem. It needs to be understood that rehabs are part of the process.”

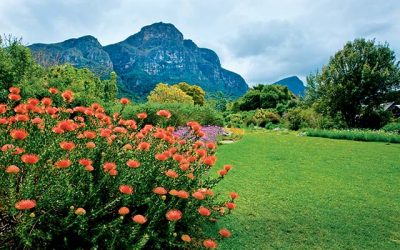

It was just outside Somerset West, along Winery Road, that winemaking and sobriety finally did meet. Rustenburg Addiction Care is South Africa’s upmarket rehab pièce de résistance.

As we drove down the brick road into the facility, which was shrouded by a canopy of trees, a small herd of springbok dined on a manicured lawn. Here, on this Dutch colonial estate, there is a French chef, two swimming pools, a rose garden and – never mind a duck pond – a small lake with weeping willows that look on to the vineyards beyond.

This would have been Johnny Graaff’s next treatment centre. But he moved to London, abandoning it along with Montrose Place, which, according to an attorney for the family, was repurposed for “business reasons”. What he left behind allowed “a little piece of rehab paradise” to fall into Meyer’s lap.

It’s clear Meyer is proud of what he’s built, revelling in his latest treatment acquisition. But throughout all his successes Meyer is most proud of his own recovery from an addictive disorder.

“At the end, if I had died, it would have been a relief. To carry on the addiction had become such hard work and I didn’t know how to get out of it. Sometimes you wish death would embrace you. But I went to a treatment centre where the disease-model theory began to make sense and I realised this was something I could recover from.”

And that, says Meyer, is what is really what treatment centres –whether they come with high thread counts or threadbare sheeting – are offering.

“The fundamental commodity of what we sell, what the client is buying from us,” he says quite simply, “is hope.”

Tanya Pampalone is the executive editor of the Mail & Guardian. She oversees print and digital narrative features and special editions. Follow her on @tanyapampalone