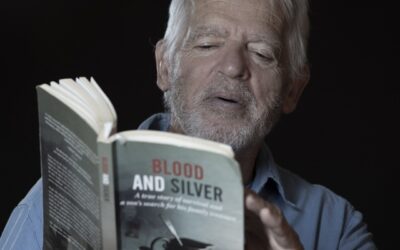

THR’s awards analyst Scott Feinberg chats with the 84-year-old Ahmed Kathrada, who was one of Mandela’s oldest and closest friends and was present for many of the events chronicled in the film Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom.

“I think that it’s a very good portrayal of the book,” Ahmed Kathrada, 84, told me by phone from his home in South Africa when I asked him last week what he thought of the new film Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom. Noting that he has seen it several times, he continued, “Naturally, with a book like that, which encompasses several hundred pages, it’s not easy to include everything about his life. But I think it was quite a fair portrayal. I was quite satisfied with it.”

A review like that could, conceivably, have come from anyone — but Kathrada is not just anyone. He was one of Nelson Mandela’s oldest and closest friends and witnessed first-hand much of the journey that is chronicled in Justin Chadwick‘s film, which stars Idris Elba as Madiba and Naomie Harris as his second wife Winnie. (Kathrada is portrayed in the film by Riaad Moosa.)

Kathrada and Mandela had been friends for 67 years at the time of Mandela’s death on Dec. 5; Mandela knew him as “Kathy.” They challenged Apartheid together as far back in the 1950s and 1960s. They were arrested at the same political gathering on July 11, 1963. They were tried and sentenced to life in prison alongside one another at the Rivonia Trial from 1963 to 1964. They were imprisoned together in the same jail block on Robben Island, the Alcatraz of South Africa, for 26 years. (Kathrada was freed one year before Mandela.) They were both elected to political office in South Africa’s first free and fair elections in 1994, Mandela to the presidency and Kathrada to the parliament, from which he served as one of Mandela’s closest advisors during Mandela’s historic single term. And they were both in Qunu, Mandela’s rural birthplace, on Dec. 15, the day of Mandela’s funeral, at which Kathrada delivered the most moving eulogy of many that were given to the late leader.

As the son of a South African attorney who represented political prisoners housed on Robben Island during the 1970s, and as someone who has personally spent a considerable amount of time in South Africa and considers it a second home, I have found the last few months to be something of an emotional rollercoaster. Back in Sept., I felt immense pride as I sat in a massive theater at the Toronto International Film Festival and watched Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom; I couldn’t imagine a better tribute to a man who had come to be respected and admired by more people than just about anyone else in the world. Then, in Dec., I, like the rest of the world, was deeply saddened to learn of Mandela’s death; to be sure, he was 95-years-old and ailing, but his passing marked the end of a great life and the beginning of a period of great uncertainty for the nation he kept together when many around him thought it would fall apart. And then, in Jan., I was offered the amazing opportunity to speak by phone with Kathrada, who represents one of the last ties to a truly momentous period, in order to get his unparalleled perspective on Mandela and Mandela.

Kathrada is a man who can not only talk about South Africa’s tumultuous history but who has lived it. Now, with Mandela gone, he is part of the conscience of his nation, a responsibility he honors by giving tours at the prison in which he was once incarcerated and by reminding his countrymen — as he did in front of the world at Mandela’s funeral — not to forget, in the commotion surrounding the death of Mandela and its aftermath, the values and objectives for which Mandela — and Kathrada himself — lived.

* * *

The Hollywood Reporter: Do you remember what led you to become politically active for the first time?

Kathrada: Well, you know, I was literally swept into politics at a very young age when I didn’t even really understand what politics is. Where I was born, in a rural area, I was not allowed in the white school or in the black school, and there was no Indian school, so, at the age of eight, I had to be sent away from parents all the way to Johannesburg to go to school. That’s over 200 kilometers. In retrospect, that was Apartheid. But at that time all I could do was to question why I could not go to school with my friends — because, as youngsters, you don’t know color. My friends were white, were colored and were black, and when it came to school I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t go to their school and had to go all the way to Johannesburg.

My understanding is that, at a very young age, you became a part of the Indian Congress. How did you come to join that organization?

Well, what happened was, at a very young age, in the area that I lived, there was a club run by the Young Communist League, and it was through that club that I joined the Young Communist League. There were no other youth organizations at that time; they came later. But, to cut a long story short, that’s how I really started in politics — in the Young Communist League and, later on, of course, in the Indian Youth Congress and in the South African Indian Congress. As you may know, there was different legislation for different communities. That gave rise to an Indian Congress, an African Congress, a Colored Congress, because different laws applied to different communities. So I belonged to the Indian Congress.

Wasn’t it when the Indian Congress and the African National Congress first started interacting that you first met Nelson Mandela?

Yes. I was already in the Indian Youth Congress at the time. I met him through his university colleagues, who were Indians whom I knew. He used to frequent their place and that is where I met him in 1946, 68 years ago.

What were your first impressions of him?

My abiding impression of him, which lasted all my life, was his ability to relate to me as an equal, so much so that the questions he asked me made me feel so comfortable that I could go back to school and boast to my friends that I met a university student who treated me the way he did. That is how I remembered him all my life. He had an ability to treat everybody as equals.

Is it true, though, that when you two first met, you initially sort of challenged him a little bit? You wanted to debate him, didn’t you?

Yes. That was the one and the only argument we had. I’m 11 years his junior and it was on a question of a strike that was jointly organized by the Indian Congress, the Communist Party and the ANC. He belonged to the ANC Youth League, and the Youth League was not racist but it was against cooperation with the Communist Party or with other liberation organizations. We met on a street and got into an argument where foolishly, at my young age, I challenged him to a debate, and that led to a little argument. But that was all history and we teased each other all the years on Robben Island because the strike which they opposed was successful, but unfortunately eighty people were killed in that strike. And, of course, that led to a closer relationship between Mr. Mandela, the ANC Youth League and the other organizations. That was the genesis, I would say, of the Youth League changing its views from non-cooperation with other organizations to one of cooperation.

What stands out the most in your memory of July 11, 1963, the day on which you, Mandela and the other future Rivonia Trial defendants were arrested?

Well, you know, we were together in three of the major trials of the ’50s and ’60s. The first was the Defiance Campaign trial of ’52, in which 20 of us were sentenced to nine months imprisonment, but it was all suspended so we didn’t have to serve the sentence. Then, of course, from 1956 to ’61, there was the Treason Trial, which started off with 156 accused, but from 1958 to ’61 there were only 30 of us left, and in 1961 all 30 of us were acquitted. And then, of course, came the Rivonia Trial in which we were sentenced to life imprisonment. That was in ’63. Well, you know, at that time, for the pre-trial period, there was a law which held that detainees were to be kept in complete isolation, with no visits from lawyers, etc., except the police, who came to extract information. And, at that time already, the police had warned me that if I didn’t give them information I would be sentenced to death, so when we eventually saw our lawyers for the first time in 1963, the lawyers cautioned us about the same thing — that we should prepare for the worst: a death sentence. And that is how the trial was conducted, as a political trial and not a criminal trial. In other words, the cue was taken from Mr. Mandela out of that four-and-a-half hour speech in court which set the trend of how the trial should be conducted. In other words, for those of us who went to the witness box, you proclaimed your political beliefs; you didn’t apologize for them; you didn’t ask for mercy; and, in the case of a death sentence, you didn’t appeal. That is how the whole trial was conducted until the very, very last day, when the death sentence was suspected among the lawyers and among us. But, fortunately, the judge pronounced a life sentence, and that’s how we landed at Robben Island.

My sense, from other interviews that you’ve given and other things that I’ve read, is that Mandela really emerged as the leader of the defendants during the Rivonia Trial. Were you and the other defendants consulted about his now-famous speech before he gave it?

All of us agreed entirely with that speech. Of course, it was given to our lawyers. Fortunately, our lawyers were also political people and they agreed with it. All of us agreed with the speech because, as I said, the expectation was death, and as Mr. Mandela said at some stage, “If we have to die, we should die in glory.” So that is how the whole trial was conducted until the very last day, when the judge pronounced life imprisonment.

When the judge did make that ruling, how did you feel? On the one hand, I’m sure it must have been a relief not to have to face execution, but on the other hand spending the rest of your life in prison cannot have sounded very good either…

Well, you know, there was a collective sigh of relief when we heard that we weren’t going to die.

Did you ever think, at that time, that it was realistically possible that you might one day be freed, or did you truly believe that you would spend the rest of your life imprisoned on Robben Island?

Well, you know, according to the law at that time for political prisoners, life meant life; criminals or common-law prisoners could be released after 15 years. So we had to adjust to the situation that we were gonna be on Robben Island for a very, very long time. And it did not take us long to adjust to that situation. In other words, right from the beginning, we had to adjust ourselves and make life as near to normality as possible. That is how we treated our imprisonment.

While you were imprisoned on Robben Island, were black people and Indian people treated the same way or differently?

There was Apartheid between different communities. As I said originally, there were laws that applied to Indians, laws that applied Coloreds, laws that applied to whites and laws that applied to blacks — different laws. In the trial there were eight of us. But our eighth colleague, Denis Goldberg, being white, was not sent to Robben Island; he was with other white political prisoners. The seven of us were flown to Robben Island. I was the only Indian among the seven of us and the youngest of the seven. I was given long trousers, whereas all my colleagues who were older than I was — my leaders Govan Mbeki, who was 20 years my senior, Sisilu, who was 18 years my senior, Mandela, who was 11 years my senior — had to wear short trousers. I was given long trousers, according to the regulations. And when it came to food, at breakfast time we had the same food — porridge, soup and coffee. I was given a little more sugar than Mandela, but less than Denis Goldberg — but Goldberg was in Pretoria. I was given a quarter-loaf of bread every day; Mandela got bread for the first time after 10 years. Incidentally, if I may, there’s a book published by the University of Kentucky called No Bread for Mandela. That is my book — my memoirs — which were published in 2011. It is a biographical book. It’s the same book that was published in South Africa, but the title was different, that’s all.

During those many years that you were on Robben Island with Mandela, what sorts of interactions did you have with one another? And did anything about the way he was handling his imprisonment stand out to you?

We had four of the most senior leaders of the ANC with us among the eight of us, and right from the start Mr. Mandela said, “We are no longer leaders. We don’t make policy. We don’t give instructions to the people outside. Our leaders are in exile. The National Executive of the ANC” — that is, Oliver Tambo and others — “they make policy. Our job is to concern ourselves with prison conditions.” Once he said that we are no longer leaders, we are ordinary prisoners, that is how he comported himself throughout. No preferential treatment. Whatever chores that we had to carry out, he was there with us, working with pick and shovel in the quarry for 13 years. He could have easily been exempted on the grounds of his high blood pressure; he did not ask for that. He was with us for the full 13 years. When there hunger strikes, he did not ask for any exemption; he was with us for the hunger strikes. 13 years after we were in jail, he was offered release provided he go and live in the Transkei; he refused. In 1985, of course, there was a general offer to release all of us — all political prisoners — on certain conditions; the vast majority refused to be released on conditions. So that is how he finished 27 years and the rest of us 26 years.

When you were freed in October of 1989, could you believe it? Was it very difficult to adjust to being back in society? And what motivated you, after an experience like that, to get back into politics?

We were released suddenly. A few days before that, President de Klerk made an announcement that eight people were going to be released, but he did not say when. That was about five days before our release. So we were flown to Johannesburg on a Friday — to the prison there — and on the Saturday night, the head of the prison came to us and said that he had just received a fax from prison headquarters to saying that we were to be released tomorrow. Our first question was, “What is a fax?!” You know, for 15 years we didn’t have newspapers, and only later on we had television, so we could imagine this called “fax” but we didn’t know how this thing worked. So we came out into a different world altogether. Everything was new. Microwave ovens, ATMs, computers — the whole road system was different. Everything was different. In our case, we were not given a chance to adjust. From day one, media from all over the world were there and there were just interviews after interviews, and it just carried on. And that’s how we adjusted to politics again.

When Mandela gave his inaugural address in 1994, he, as you know, shared his dream of “a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.” It seems to me that, in some respects, South Africa has made great progress toward that vision but, in others, it still has a very long way to go…

Yes. The policy of the African National Congress and the government entrenched in the constitution was for a non-racial, non-sexist, democratic South Africa. In the five years of his presidency that I was in his office, he concentrated on nation-building, reconciliation and one united nation. That was his concentration. Among the first things he did, as you may have heard, was he invited the widows and the wives of Apartheid-era presidents and prime ministers to tea with him — and then when Mrs. Verwoerd was not well, he flew to her to have tea with her. It may sound like a small gesture after 20 years, but at that time it was quite significant. And it was the beginning, you can say, of his true devotion towards a non-racial South Africa. There was widespread fear, especially among our white compatriots; because of all sorts of movements, many, many left the country, and they had to be reassured that the fears they had about a black president were unfounded. And there were these gestures, which were important in themselves to reassure our white compatriots that there would be no punishment, that there would be no Nuremberg Trials, that there was a policy of forgiveness, no bitterness, no revenge, a unity towards one nation. That was his concentration during the five years and after.

Do you feel that Mandela’s successors — including President Zuma, who I know was imprisoned for 10 years on Robben Island while you and Mandela were also there — share the same values and objectives that Mandela had when he was president? It seemed from your speech at Mandela’s funeral that you feel there is room for improvement…

Well, you know, my approach to this whole matter is that I don’t concentrate on individuals. Individuals come and go. My concern or worry would be if there is any attempt to change the fundamental policy of the African National Congress. Individuals have their own style of doing things, but they come and go. The policy is entrenched in the constitution of a country, and I’d be very worried if there was any attempt to change that constitution. Otherwise, I repeat, individuals will come and go.

With regard to the movie Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom, were you in any way consulted or involved with the making of it? And is it a movie that you’re happy with?

I think that it’s a very good portrayal of the book. I have seen it several times. Two weeks ago, we saw it in Boston; a special premiere of the film was held in Boston, which I attended. So I saw it several times and I think it was a very good portrayal of the book. Naturally, with a book like that, which encompasses several hundred pages, it’s not easy to include everything about his life. But I think it was quite a fair portrayal. I was quite satisfied with it.

What do you hope the legacy will be of Mandela, yourself and others who gave up so much for the cause of a better South Africa?

Well, you know, Mandela did not make policy as an individual; he was wedded to the policy of the organization, and the policy of the organization is not only in the constitution of the ANC but in the constitution of the country. Now, we have many challenges — we’ve only had 20 years as a democracy. Apartheid is no longer the first challenge, but the challenges are poverty, hunger, unemployment, crime, disease, education — those are the challenges that we have to face now. And, as I say, the policy has been reaffirmed by the ANC at various conferences, and I have the hope and the wish that they’ll continue. Now, I am just a rank-and-file member of the ANC; I stood down in 1997 from the leadership of the ANC. I am just an ordinary branch member. But I have all the hope that whoever is elected will carry on with the policy — the fundamental policy — of the ANC.

Scott Feinberg via The Hollywood Reporter