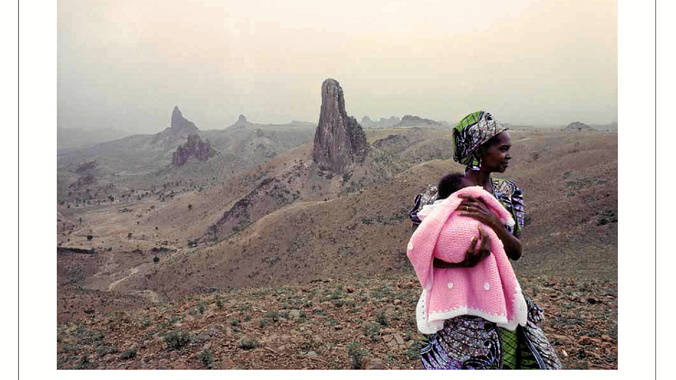

Photographer George Hallet has devoted his career to making images of people many others would prefer to ignore, observes Yazeed Kamaldien, in an interview to tie in with his impressive retrospective at IZIKO South African National Gallery.

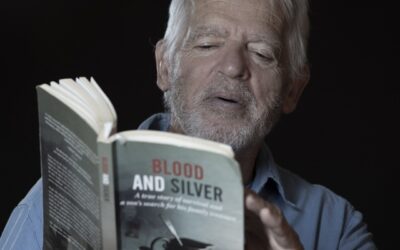

George Hallet does not want his photograph published in this newspaper – or any other, for that matter.

“I prefer being a fly on the wall,” he says.

Hallet has been “invisible” for just over four decades, taking pictures to make sure unseen communities get noticed. “A woman asked me: ‘George, why are you always photographing black people?’ I replied: ‘Because everybody else is ignoring them.’

“I photographed Moroccans in France. I went into their mosques. I photographed what people in France called peasants. But I treated them with respect. They were old enough to be my parents.

“I photographed hippies in conservative English towns. I was one of them; my hair was long. The Gypsies were another thing. And when I was in Paris or Amsterdam I photographed blacks and whites mixing. I worked on anti-racism projects.”

Hallet’s photos have been exhibited and published in books worldwide ever since he first picked up a camera in 1965 at the age of 23.

Now a chance to dig into his archive has emerged. The result is a showcase of almost 200 images in a retrospective exhibition that opened at the South African National Gallery in Cape Town last week.

It includes plenty of photographs produced during the 25 years he spent in exile, before returning home permanently after South Africa’s 1994 democratic elections.

Hallet was a young man, working in the administration office of a shipping company at the Cape Town docks, when he started his photographic career.

He met a photojournalist and together they documented the last days of District Six in Cape Town in the late 1960s when the apartheid government forcibly removed people of colour from the inner-city suburb to create a “whites only” area. Hallet, who was born and grew up in District Six, says the aim was to document the “area before the bulldozers came in”.

“I had a roll of film every Saturday morning. I had only 36 exposures for a weekend … You had only one frame per person. It’s about [choosing] the decisive moment.”

He had also been photographing weddings and doing portraits on the street in District Six before it was destroyed. This work was shown at his first exhibition, at the Artist’s Gallery in Cape Town in 1970.

Hallet’s politicisation started in high school thanks to his English teacher, the acclaimed South African author Richard Rive.

“He said we should not discuss politics in our essays because then he would be arrested. And after I met writer James Matthews and artist Peter Clark and the Sestigers [Afrikaans-speaking writers and artists who were opposed to apartheid] it was politics all the time,” says Hallet.

“We were also introduced to African-American writers. They were into black consciousness and they were ahead of us. They were an inspiration.”

When he no longer felt safe living in South Africa he went into exile and found the freedom he longed for in London in the 1970s.

As a freelancer, Hallet photographed the covers for Heineman’s African Writers Series and also worked for the Times Educational Supplement and the BBC.

Politics was never far out of his focus though. Hallet captured the life of many exiled South African artists living in Europe, including celebrated painter Dumile Feni and iconic jazz musician Abdullah Ibrahim.

Through his work, he formed links with various political activists who, like him, were also living in exile in Europe. One of the political figures he photographed in London is former South African Cabinet minister Pallo Jordan.

His political activism once led to him getting a rather unsettling phone call.

“I got a call from Scotland Yard … I was told that I assassinate South African spies. I said: ‘I’m a photographer. I’m opposed to apartheid but I’m not into violence. I don’t know where you get this information from.’ It was obviously planted.

“My friends suggested I take a break in the south of France.”

Hallet left for France, fell in love and stayed. At home in a Parisian suburb in early 1994 he had a dream about meeting former president Nelson Mandela. “In my dream, we [Mandela and I] were having lunch together but the chairs we were sitting on were balanced on their back legs. I knew a Moroccan dream interpreter. She said: ‘You will meet Mandela. There’s going to be a lot of violence in the country’.

“Three weeks later, a phone call from Pallo [Jordan]: “Hey, jy moet huis toe kom [you must come home]. I’m in Jo’burg. I want you to photograph the [April 1994] elections. You will be our official photographer. But we can’t afford to buy your air ticket. Can you buy your own ticket?’ I phoned my wife at work and said the dream has come true.”

Hallet did have lunch with Mandela and one of his images of the former president won the World Press Photo award in 1995. A year later Hallet was on the judging panel of the global contest.

He recalls: “I later asked Pallo: ‘Why did you choose me out of all the photographers?’ He said: ‘You’re good and you get the stuff without lots of lenses around your neck. You are like a fly on the wall’.”

George Hallet: A Nomad’s Harvest is on at the South African National Gallery until July 9

South African National Gallery, Government Ave, Cape Town 8001.

via Mail & Guardian and see