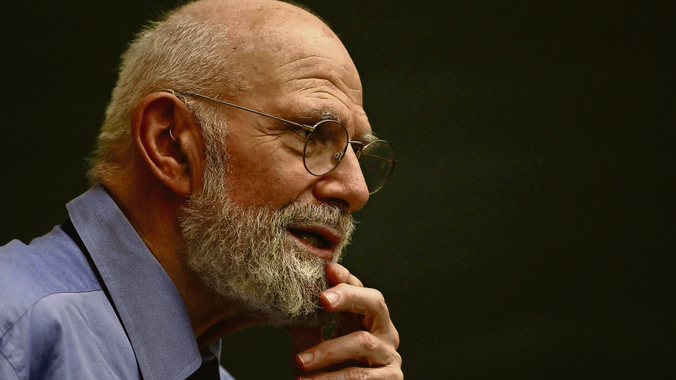

The man who wrote so compellingly of illness, Oliver Sacks, has died, having changed lives and attitude, writes Adam Zeman.

With his absorbing and accessible yet profound accounts of neurological cases and conditions, Oliver Sacks, who has died aged 82, brought the clinical science of the brain to life for countless readers. Although his first book,Migraine (1970), marked a relatively conventional beginning, Sacks’s decision to write about a neurological disorder with complex psychological precipitants and concomitants, and one from which he himself suffered, pointed in the direction of his future interests.

His second book, Awakenings (1973), crucially encouraged by his publisher Colin Haycraft at Duckworth, appeared when Sacks was 40 and brought his work to a wide audience.

Effusively praised by the critics, it describes the effects of L-Dopa, then recently recognised as an effective treatment for Parkinson’s disease, in a group of patients who had lived in something close to suspended animation since the epidemic of the “sleeping sickness”, encephalitis lethargica, swept the world at the end of World War I.

In the words of metaphysical poet John Donne, one of Sacks’s literary masters, Awakenings depicts his patients’ “preternatural birth, in returning to life, from this sickness” – a birth sometimes fraught with awful tribulations. Awakenings became the subject of the first documentary in the ITV Discovery series (1974), and a successful film, starring Robert de Niro and Robin Williams.

Sacks’s many subsequent books ranged across and beyond the territory of clinical neurology, but his work always remained rooted in his fascination with the brain.

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (1985) and An Anthropologist on Mars (1995) are collections of essays on patients with disorders of sensation and perception (such as the agnosic Dr P, who mistook his wife for a hat, and the colour-blind painter Mr I); of memory, language and movement (like “Witty Ticcy Ray” and the surgeon Dr Carl Bennett, both sufferers from Tourette syndrome, with its combination of intense physical tics and psychological compulsions); and of “social cognition” more broadly, as in the case of the autistic academic Temple Grandin, who described herself feeling as if she were “an anthropologist on Mars”, so mysterious did she find the ways of her fellow humans.

In Seeing Voices (1989), Sacks explored the experiences of the deaf; in The Mind’s Eye (2010), he returned to disorders of vision, a subject rendered highly personal for him by the loss of vision in one eye to a retinal melanoma, the ultimate cause of his final illness. Hallucinations (2012) allowed Sacks to explore the territory of the imagination, drawing partly on his own experience of migraine, LSD and drug withdrawal. Musicophilia (2007) is a neurologist’s tribute to a lifetime’s enjoyment of music, illustrating its power using Sacks’s usual method – the arresting, emotionally muscular, case history.

The importance of individuality in medicine

He also wrote prolifically for periodicals including the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books and inspired an abundance of work in other media. He appeared in documentaries, winning recognition as a highbrow but appealingly bearish TV personality. His extensive televised travels took in the Western Pacific island of Guam, famed in neurology for its high prevalence of a complex neurodegenerative disorder that Sacks and others have attributed to exposure to an environmental toxin.

See full report in the Mail & Guardian