Paintings by Jill Trappler and multimedia and prints by Eunice Geustyn, in a show titled Half Light at AVA Gallery, reviewed by Danny Shorkend.

The staggering number of abuse of woman and children in South Africa is of great concern and a depressing reality.

Eunice Geustyn’s prints, installation and multi-media works address such issues, while Jill Trappler, in a rather more abstract way deals with that which is on the cusp of seeing and not seeing in her paintings, wherein there is a sense that one ought to see reality, however murky or formless it may appear.

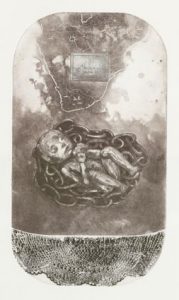

One of Geustyn’s series entitled “swallow”, incorporating rather involved technical methods points to a rather neat, polished and perhaps beautiful veneer.

Yet it is just a veneer as the titles and content reveal that the artist is concerned with the loss of innocence, neglect and the stark reality of psychological and physical torment. The well-worked backgrounds suggest a confused state of being, the presence of a shadow, the disgusting luring of children into a depraved world. Her works are a kind of literal narrative, yet complex in here obsession with creating beautiful surfaces and loaded iconographic meaning.

It is difficult to see the link between the two artists. I would suggest that it is the incantation of a liminal space, a as-yet-not-seen form that one can detect in Trappler’s abstract works which in turn mirrors that the discussion and debate around the issues that Geustyn presents, such that they are not clearly recognised or solved. It is as if the terrible reality just continues indefinitely, as if the grid-like, endless depth that one can detect in Trappler’s paintings points to a capitulation to this endless violent cycle. That there is but continuous weaving, colours and line that just iterate without cessation, and an overall lack of centre and focus (for the good).

Geustyn’s installation consisting of sea sand and 23700 medical vials with words therein alludes to the number of cases of child abuse in South Africa per year. It is at once a kind of documentation as well as a work that tries to heal the wounds. The viewer can only but engage with the work, having to step over the “line in the sand” as one is attracted by the glint of the vials and other aesthetic devices.

The round of the aesthetic attracts only to repel, just as Trappler’s paintings draw the eye in only to send it, so to speak in a number of directions – again reiterating the point that the ills of society have not been dealt with in a sustained and focused manner. Perhaps this interpretation stretches the issue somewhat and in fact all one can perceive is a superficial presence. Yet art is coded; signs that lead one from presence effects to meaning effects and once Trappler’s paintings are contextualised side by side with the narrative of Geustyn’s works, perhaps such a reading does indeed obtain.

Trappler’s work requires a kind of optical adjustment, the dawn of a new light, the passing phases of light, the gloom of darkness and shadow. But, in accordance with the argument above, it is precisely this lack of stasis, of visible clarity that the ominous cause of objectifying, dehumanising and violence toward woman and children prevalent in South African society and indeed globally, is evident. This is also reflected in the titles that Geustyn gives to a few of her prints – “no means yes”; “have a drink” and “boys night out” – in all cases recalling the crude realities that plague society.

On the whole, the exhibition is upsetting, but perhaps the role of art is precisely “realism”, that one should not hide the realities that exist and revert to a kind of “idealism”, where classicism and the hankering after aesthetic beauty need not be the occupation of the artist. That the artist is the voice of conscience.

Yet both the expression of classic beauty and the idea of the artist as prophet, as seer, have been debunked, so much so that one can call into question whether expressing such negative facts of existence creates awareness and motivates change.

What one can say is that it probably does encourage conversation and at least some awareness of the issues. And the art/craft is itself highly accomplished.

WHERE: AVA Gallery, Church Street, Cape Town 8001

WHEN: until 30 September 2016