SA’s gun culture inspired Ralph Ziman to fetishise the Kalashnikov rifle in his gallery installation, “Ghosts” which takes aim at the arms industry, reports Jeremy Kuper.

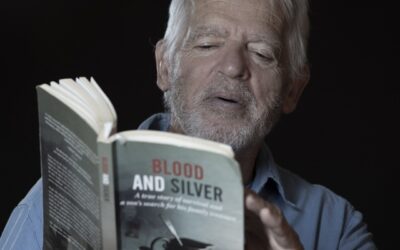

Best known as the director of the 2008 South African crime film Jerusalema and for his music video work with such top stars as Tony Braxton and Michael Jackson, Ralph Ziman’s new art installation Ghosts is a powerful comment on the global arms trade and the worship of guns in South African society.

The work includes an extraordinary series of photographs showing men dressed in Day-Glo outfits toting wire-and-bead AK-47s, which are exhibited alongside the imitation weapons. Zimbabwean street artists made the beaded AK-47s – and posed for the photographs – that are part of Ralph Ziman’s exhibition, ‘Ghosts’.

The exhibition opens at Muti Gallery in Cape Town on April 24.

The presentation of Ziman’s photographs – imaginary rebel warriors with their stylised beaded guns and Afrofuturist costumes – suggests the fetishisation of the weapon. I can’t help seeing something otherworldly at play in this deification of the Kalashnikov.

The idea came about when Ziman noticed the wire animals made by Zimbabwean street-art vendors outside the Goodman Gallery in Jo’burg. He decided to commission them to make him a wire AK-47. “To see what it would look like,” he says over Skype from Los Angeles.

“They’re amazing, really talented guys. I started because I had this idea: I wanted to see what it would look like to make an AK-47 out of [wire and] beads.

“They laughed and then they quoted me an enormous amount. They said it was very expensive because it was a very complicated thing to make. And I said: ‘OK, fine, let’s do it.’

“The first week they made one and the next week I went back and they made me three or four. And in the end it was like 10 or 12 guns a week,” he says.

Ziman also acquired a consignment of empty AK-47 shells and these were sent to a group of women in Mpumalanga, who work with the wire sculptors, to weave beads around the wire AK-47s and to produce replica bullets to go with the guns.

The process was very organic, Ziman says. “We kept changing the designs. I thought it would be nice to do them in series. I would do 10 red AK-47s, or nine, so you’d get three rows of three. And then we did multicoloured ones.

“We started off with a lot that looked so realistic. They were interesting because when you see guys posing with them they look like real guns and these guys were [like] real rebels.

“In the end I had something in the region of 200 guns, which I put in a container and shipped back.” Ziman was able to track them all the way back to Los Angeles using GPS, in a reverse of the normal flow of weapons out of the United States.

The US is the world’s largest arms dealer, followed by Russia and China, he says. “Those countries are making weapons and they’re shipping them into Africa and supplying both sides of the same conflict.”

The weapons are often provided on credit and whoever wins then has to spend their gross national product paying these debts off with interest for years and years.

“The arms don’t go away; they just get recycled.” Wars like the one in Mozambique, and the end of apartheid, left the region awash with AKs. He mentions how some returning Umkhonto weSizwe guerrillas buried their weapons instead of turning them in, as a precautionary tactic in case the new government did not turn out as they expected.

Some of these weapons were later used for cash-in-transit heists and hijackings – something Ziman references in Jerusalema – “not for political purposes”.

Ghosts is not just a powerful critique of the arms trade in Africa, but also of Jo’burg’s Wild-West image. “It’s that pervasive gun culture and the fact that there’s weapons everywhere – and you wonder where all the weapons come from. Like somebody’s opened this tap and they just flow in.”

Ziman’s righteous indignation when it comes to South Africa’s tainted multibillion-rand arms deal is another influence on the installation. “I don’t think heads rolled enough,” he comments. “I just think it was really sad that all the people that had supported the government and stood by them through years of austerity didn’t get to benefit, unlike certain figures close to the leadership.”

He points the finger at Germany, France and Sweden as the main culprits in this case. Supplying submarines, naval ships and fighter jets, which were far more expensive than the preferred option chosen by the South African Air Force. “What are they doing selling weapons like that to South Africa, and what’s South Africa doing buying them?”

Interestingly, the beads for the work initially came from China. They are made of glass and tend to be smaller and more uniform in shape than African ones. The wire sculptors use them because they are cheaper than local beads.

“Somewhere along the line we’d swapped to African beads, and the cost of the weapons went up at that point. When I’d started I had no idea, I’d assumed almost automatically that all the beads were made, maybe not in South Africa, but at least in Africa somewhere. It’s crazy, you have beads coming in from China that are much cheaper than anything that’s made locally.”

The wire-animal traders themselves posed for the photographs, but their identities are hidden. Their faces are covered with Balaclavas or masks, or deliberately underexposed. “You give someone a gun and he knows how to pose, he knows how to stand,” Ziman says, “probably from the movies.”

“There is this mythic quality of the AK-47 in South African culture. The AK is the subject of protest songs and possesses a certain mystique, but it is, of course, also very frightening.

“Its savage beauty can be quite disturbing in a way. I think the beauty is seductive and it pulls people in. But if it makes you think about it, or if you realise what you’re looking at is not that beautiful [that is a good thing],” says Ziman.

“There’s a seductiveness in the guns, in gun culture – the way people collect them and fetishise them and pose with them. There is that, definitely. And I think you need a striking image to draw people in.”

Via Mail & Guardian

WHERE: Muti Gallery, 3 Vredehoek Ave, Cape Town 8001

INFO: T 021 465 3551