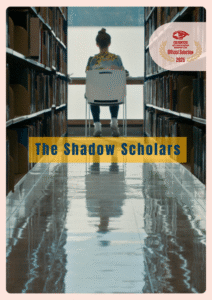

Shadow Scholars takes an in-depth look at the contract-cheating industry, which involves tens of millions of students around the world submitting essays provided by online academic writing services – with ‘clients’ including people studying science and medicine at some of global academic’s most prestigious institutions.

Due to its high level of education and the poor prospects for its graduates both in and outside the country, Kenya has become the world leader in supplying expertly written papers, at speed, to university students around the world, particularly in the United States. In exposing the scope and scale of contract cheating, the film reveals the broader colonialism and racism that continues to keep gifted Kenyans from competing on an equal playing field with graduates from the richer countries. Featuring interviews with writers, the students who use their services, and members of the global academic communities – including the revered Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o – The Shadow Scholars is a thought-provoking and eye-opening film.

Director Eloise King | United Kingdom | 98 min | 2024

Director Eloise King | United Kingdom | 98 min | 2024

WHAT: The Shadow Scholars – Encounters 2025

WHERE: Ster Kinnekor, V&A Waterfront, Cape Town 8001

WHEN: Wednesday 15 June – 18:15 | Encounters 2025 ends on 19 June

BOOKING: Webtickets

INFO: Encounters 2025 programme

The Thinking Game and Shadow Scholars by Christopher Thurman BUSINESS DAY 25/5

I’m a writer. I write for money. I write for pleasure (not including emails). Writing gives me a challenge, a sense of meaning, a purpose. Part of my job, until recently, was teaching people how to write – or how to think by writing. This also meant teaching

people how to read properly. For a decade or two, another unpleasant sub-activity of my day job as a university professor was figuring out whether my students had actually written what they presented as their writing. Now this task has morphed into figuring out when the intelligence on display in their essays is human, and when it is artificial.

The boom in large language models (LLMs) and the constantly shifting ground of artificial intelligence more generally cause permanent low-level anxiety about my writerly and academic vocations. So it’s unsurprising that of the 64 films being screened

at this year’s Encounters documentary film festival, I was immediately drawn to two in particular.

In The Thinking Game, director Greg Kohs follows former wunderkind and now tech industry leader Demis Hassabis, who has led a series of teams pioneering the terrain of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI): that is, getting AI to the point where a machine can tackle any intellectual task without prior training (such a machine would also, of course, be superior to humans in any given task).

Starting with video games, progressing to the complex board game Go, and eventually attaining real-world success through protein structure predictor AlphaFold – for which he and colleague John Jumper were awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in

Chemistry – Hassabis gives one the impression of being a true visionary: ambitious but not megalomaniacal, idealistic but not naïve, confident in reaching his goal but not indifferent to the attendant risks.

I will admit that the film’s sympathetic depiction of its subject helped to mitigate against the panic and anger that rise in my chest when I think about tech bros, money and politics. Not everything in this field is tainted by Machiavellian schemers and corporate greed. Was Peter Thiel an early funder? Yes. Did Google take over? Yes. (Hassabis is CEO of Google’s DeepMind.)

But are most of the people actually working on these AI projects committed scientists with global problem-solving aims like

reducing plastic pollution and beating deadly diseases? Yes.

Still, even if technological development is morally neutral, its applications – from sustainable food supplies to military might – are not. Hassabis spends lots of time in this film riding trains. The visual conceit may be strained but it is nonetheless evocative.

As we hurtle towards an unknown future, are we in the expert and benevolent hands of drivers like Hassabis, or are they merely brilliant co-passengers along for the ride?

Eloise King’s The Shadow Scholars, by contrast, takes the viewer on a much slower journey. Oxford professor of Sociology Patricia Kingori returns to Kenya, the country in which she was born, to meet just a few of the approximately forty thousand people who have found employment producing essays and dissertations for university students around the world.

It is a fascinating but heartbreaking experience for Kingori, who greatly admires the ability and work ethic of the Kenyan writers. Given the country’s “overqualified, underemployed population”, it makes perfect sense that they should fill this economic niche.

But the anonymity of their doubly-hidden labour, Kingori explains, demonstrates international power dynamics and the (racially loaded) narratives that continue to serve the global north.

Firstly, these young African scholars have to pretend that they are white and Western in order to obtain writing commissions – that is, in order to be considered “reliable”. They then produce essays for customers who will ultimately receive degrees

based on their ability to pay for a service (some 37 million students have done so, undetected by their universities despite the digital footprints left by these transactions).

This industry will soon be a thing of the past; ChatGPT is killing the essay mill. But the Eloise King film tells a bigger story, a story of mothers and daughters, of aspirations and frustrations, of changing perspectives about what is real and what is fake.

There are also devastating insights into histories of migration, inequality and exploitation. “They want our ideas,” the

Kenyans observe, “they just don’t want us.”