A monograph on the work of artist Sue Williamson coincides with a new show at Cape Town’s Goodman Gallery, writes Chika Okeke-Ogulu.

The idea of “aesth-ethics” is crucial to an understanding of Sue Williamson’s work.

This is evident in the series of works for which she gained early critical attention in apartheid-era South Africa; works that, although they were included in Resistance Art in South Africa, stretched the horizons of “resistance art”, invariably extending the meaning and imaginative possibilities of the “culture as a weapon of struggle” mandate.

Consider, for instance, the structural ordinariness and conceptual power of her first major work, The Last Supper (1981), a gallery installation of rubble gathered from the demolition sites of Cape Town’s District Six and surrounded by six chairs draped in white borrowed from Manley Villa, the Ebrahim family home that had been marked for destruction as part of the racist government’s promulgation of its Group Areas Act.

Three photographs on the wall of the Gowlett Gallery showed the Ebrahims celebrating Eid in their home. At a time when South African photographers and journalists testified to apartheid’s systemic violence by depicting District Six homes turned to rubble or the traumatised inhabitants menaced by demolition crews – powerful testimonials, no doubt – Williamson chose instead to show a family celebrating in the shadow of eviction and the impending destruction of their home.

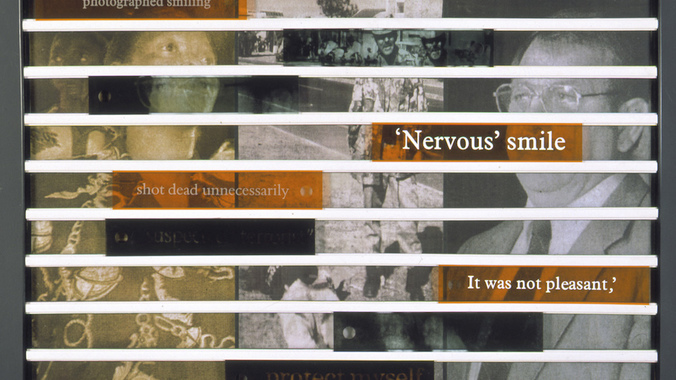

In a major work that memorialised the crumbling of apartheid’s walls, For Thirty Years Next to His Heart (1990), she colour-copied and displayed, in 49 artist-designed frames, the complete pages of a black man’s passbook, perhaps the most infamous document produced by apartheid. In these landmarks of anti-apartheid art, she used the photographic image or politically charged document to insist on the dignity, substance and courage of both the oppressed coloured and black South Africans and their white allies.

Williamson has continued to explore, untangle and lay bare moral knots and ethical complexes in today’s world, just as she did during the decade of “resistance art”.

This clearly suggests that she did not quite heed Sachs’s call for a radical change in post-apartheid art. She did not believe, I suggest, that the work of engaged contemporary art was, or is ever, done simply because a particular political ideology and system had expired in her homeland and in the human society.

In any case, if Williamson did respond to Sachs’s call in 1989, it took the form of reimagining her community as the human family, not just the post-apartheid South African world still scarred by its traumatic past and new challenges.

This is an edited extract from Sue Williamson: Life and Work, edited by Mark Gevisser and published by Skira Editore.

See Mail & Guardian