Nobhongo Gxolo explains why visiting Cape Town’s Castle never made it onto his bucket list.

Just over a decade ago the movie The Skeleton Key came out. There was a haunted house, malicious ghosts, and a line that stuck: “But I heard it can’t hurt you. It can’t hurt you if you don’t believe.” Not believing has never felt like a safe space, but rather a conjuring. A challenge to the spirits to show themselves; to make their presence felt with hair standing to attention on the neck, the flesh spouting a miniscule mountain range of its own accord.

This is why visiting Cape Town’s Castle never made it onto my bucket list. The murder and torture contained in dark chambers has diffused into the walls and left a stain.

You feel it. Rumours of ghosts run rampant with reported sightings and eerie, inexplicable occurrences. Even security patrolling the grounds stay away from certain places the light doesn’t reach while on the graveyard shift. When it became time to visit this place, the sky was overcast with Table Mountain barely visible. On the advice of a friend, I burned impepho beforehand and the plumes catalysed some comfort. Then a prayer. Protection from the restless spirits was paramount.

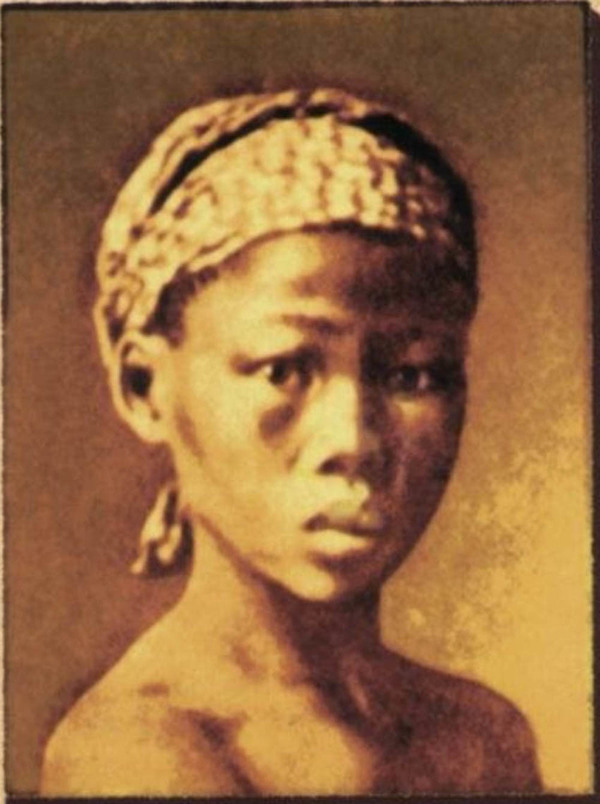

Krotoa, better known to the Dutch as Eva, because upon baptising her they had to find a name more palatable with which to summon her, one their tongues did not have to twist around – was buried at the Castle. She died at 32 in 1674. It would not be a leap to imagine that her spirit too wanders the expansive grounds. Later, her remains were exhumed and reburied at Die Groote Kerk.

On August 19, Defence Minister Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula, in collaboration with the Ministry of Defence and Military Veterans as well as the army’s Castle Control Board which runs the Castle, held a memorial service in her honour. The event had been planned, deliberated upon and debated over for a while before a date of convenient symbiosis between 350 Years Commemorating the Castle of Good Hope as well as Women’s Month was found.

Settling with the settlers

Krotoa was around 11 when she started working at Jan Van Riebeeck’s home as a playmate and nanny for his children, as a servant for his household, and as an interpreter for the Dutch. It is not clear how she came to leave her Goringhaicona tribe and ended up working there. Some say it could have been of her own volition. Others say she was taken from her home, while others claim that her uncle Autshumao, a Khoi trader and a shrewd and worldly businessman, bartered her for his own gain.

Doctor Yvettte Abrahams is based in the Department of Women and Gender Studies at the University of the Western Cape. She says it’s important to understand that the Khoi did not have a history of violence, of owning and selling people. That the first recorded Khoi killing was in 1510 and was as a result of an attempted slave robbery, when they were trying to protect their own from the Portuguese. “The first time they were recorded fighting was in defence of their children,” she says.

“Both the Khoi and Krotoa were constantly trying to understand the Dutch and their motivations. They were trying to figure out what made the colonisers tick. And if they didn’t it’s because slavery and violence were simply things that weren’t a part of life as they knew it. Try to consider a life where there was no hierarchy; just people. There was no royalty and there were no commoners. Consider being a generation to whom gender-based violence was news. But that in order to protect your children you needed to understand it.”

She refers to a Karl Marx quote: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.” Dr Abrahams says that Krotoa didn’t have a choice of the circumstances under which she had to make her choices. “The only choice was whether to assimilate or not to assimilate.”

Straddling two worlds

In an attempt to offer insight into her new and bewildering world, Khoisan researcher Dr Willa Boezak highlights the many firsts in Krotoa’s life. “She is the first young girl taken into a European household as a nursemaid; one of the first interpreters between the Fort and the Peninsular Khoikhoi; the first to be baptised in the state Dutch Reform Church; the first Khoi woman to marry a European – the Danish surgeon Pieter van Meerhof; and the first Khoi to receive a Christian burial in the Castle.”

Dr Boezak speaks to how, while living with the Van Riebeecks, Krotoa grew to become very knowledgeable about the Dutch way of thinking. That she vehemently disagreed with Doman, also an interpreter who initiated the first Khoi-Dutch War of 1659-60. “She knew that should her people lose the war, the Europeans would also take away their land – which is what happened. Doman was a brilliant strategist who had been sent to Java by Van Riebeeck for a year to further hone his skills as an interpreter. Ironically it was there that the young warrior of the Goringhaiqua tribe saw some weaknesses of the colonial masters. He used it as resistance in the war, but was wounded early during the conflict. It was at the end of the war that Krotoa emerged as a successful peacebroker – probably the highlight of her career at the Fort.” She was 16.

Krotoa straddled two worlds; two cultures, two ways of life, two aesthetics, two belief systems, two languages. Calvyn Gilfellan, CEO of the Castle Control Board, speaks to these opposing binaries and the respective pressures that would have ensued. “At 11 she was a child. She was obedient – to both sides, loyal and trying to please. She was both a traitor and devoted; both good and bad.”

Things fall apart

In the years that Krotoa worked for Van Riebeeck there is no record of her ever receiving remuneration. For Dr Boezak it’s not a leap to imagine that she may have received alcohol instead of money as payment for the deals she bartered. Perhaps an early iteration of the dop system.

“She is also the first abused woman who was forced into the tot system that became such a widespread practice on farms in the Western Cape. Her relatively secure life at the Fort changed radically when a successor, Commander Wagenaer, appointed Van Meerhof as superintendent of Robben Island. Her husband was killed on a trip to Madagascar with the goal to capture slaves, and for a short while she was allowed to stay at the new Castle with her three children. After alleged misdemeanours she was thrown into one of its dungeons and later banished back to the Island. Her children were taken away and put into foster care.” He continues: “One should remember that the colonists had the power to write history from their side and finally they depicted and demonised Krotoa as a drunkard, a whore and someone with loose morals.”

Gilfellan shares a similar sentiment stating that the information that exists about her is very scarce and scattered. “Her story is told in relation to men, she was not an individual – she could not stand on her own.”

The abuses Krotoa suffered have remained mostly untold. “She was trying to figure out gender-based violence, a concept that was new in a culture that was new… I can’t prove that she was raped; by Van Riebeek himself, by her husband, by others. But if you look at her behaviour she exhibits signs of it. Her behaviour makes sense through this lens of gender-based violence but not many others,” says Dr Abrahams.

Gilfellan shares an insight: By the time she died, she was orphaned; had likely been forcefully removed from her home; she’d been raped and possibly bore children as a result of these rapes; she’d lost her people, the Khoi and been betrayed by her adoptive community, the Dutch; she had been humiliated; she had lost her husband; she had become an alcoholic; she was jailed at the prison colony on Robben Island for disorderly conduct; her name had been tarnished.”

The memorial service held on Women’s Month was in recognition of Krotoa’s life.

“African people remember their ancestors, it’s not a big deal. It’s what they do. But for the Khoi it’s not part of a national identity. We almost don’t exist in a public sense. Here we are – African people doing what we do on the daily and people look at us in awe,” laughs Dr Abrahams. She continues: “We’re a landless nation without constitutional rights; it makes it difficult to remember our ancestors – without land to remember them on.”

In reference to the commemoration Gilfellan says: “My approach is confrontational and defies the idea of forgive and forget. We need to re-imagine history, how else it could have happened based on what we know and understand – the things that the history books leave out. We must highlight the spaces where we don’t have the answers. Colonialism was a brutal and armed process. There is nothing to romanticise about what happened.

“This (the Castle) was Krotoa’s last resting place. And even in her death she was dishonoured. She was harassed and her bones were moved, she was not allowed to rest. It was important that the Dutch Church owned up to this and recognise the dishonouring of her and many others. History hurt this woman and we were trying to give her her voice back. And although she was a tragic character she did survive being treated in a sub-humane manner. I think she died of a broken heart.”

This article first appeared in the Mail & Guardian