Mabrr died on May 9 2004. What she was and what she continues to mean is examined in I’m Not Your Weekend Special, writes Andrew Herold.

Bongani Madondo’s book is published by Picador Africa. Among the essays in it is That Old Brenda Magic by Andrew Herold, from which this edited extract is taken.

To get some perspective on what Brenda Fassie as a performer meant to me, I have to go back a long way, to the year 1978 to be exact and to Bob Dylan to be specific.

Along with thousands of others perched on the hard ground at Blackbushe Aerodrome in Surrey, outside London, England, I soaked up a sunny afternoon of music from the likes of Graham Parker, Joan Armatrading and Eric Clapton, waiting for the man we had all come to see. A month before I had seen Dylan perform at Earls Court, but this was something else: a massive outdoor concert that promised much.

The occasion would not disappoint. The sleeve of Eric Clapton’s Backless LP opens out on a photograph of the legendary guitarist in silhouette taken that day, looking out towards the massive crowd. If you look at the blur of faces below the neck of Clapton’s guitar you can almost make me out. I’m the guy with the Afro somewhere near the front.

Being British-born with a black South African father and a white English mother I had developed eclectic musical tastes. But as an aspiring singer-songwriter, I idolised Dylan.

During my years of living in England I had attended many concerts, but nothing quite like this. What Dylan played with his band was awesome, but as evening fell the great man treated us to a solo acoustic set of some of his best songs. Suddenly there was a communion of audience and performer I had never known before.

We who had come to pay homage at the altar of Dylan were witness to one of his most heartfelt and intimate performances. It still lived large in my mind years later when I fulfilled a lifelong dream and came to live in an apartheid-free South Africa. By this time a balding crew cut had replaced the Afro, but my passion for music remained.

Rubbing shoulders

I had been in South Africa less than a year when I accompanied my friend Sandile Ngema to the State Theatre in Pretoria where he was rehearsing with Ray Phiri’s band for a Freedom Day show. Rubbing shoulders with the likes of Ray, Hugh Masekela, Sibongile Khumalo and Miriam Makeba was a thrill for me.

After rehearsals we left, to return the following day for the show’s performance, with Sandile playing bass in Ray’s band. Once Ray’s set was over I followed Sandile outside, where another concert was under way. Not far from the theatre complex a large crowd had congregated in front of a stage at the far end of a square. Stimela were in the middle of their set, and as an ex-band member familiar with their songs, Sandile plugged in his bass and jammed with them.

As time wore on the crowd swelled. One local favourite after another took to the stage: Mango Groove, Tshepo Tshola, Yvonne Chaka Chaka … they kept on coming as I basked in the privilege of my backstage pass and joined the crowd’s applause.

Only as the sun began to set did I notice a woman sitting in a car to one side of the stage. The light from the open door highlighted the lines of her face as she smoked what I assumed was a joint.

I had heard the stories about Brenda – the unreliability, the suicide attempts, the scandals and the drugs, the run-ins with her long-time collaborator Sello “Chicco” Twala, the death of her lesbian lover. Had she come to perform, I wondered, or was she just another observer, finding reflections of her own once-illustrious career in the performance of others?

She got out of the car and walked around, a coat draped over her slim shoulders. How lonely she looked, fragile and vulnerable.

While in London I had come across her music at the homes of South African friends and even at ANC-fundraising parties, but it was while living in Zambia that I had first become acquainted with the sounds of Brenda and the Big Dudes, a big name promising big things. Songs such as Higher and Higher and Weekend Special brought their distinctive brand of Afro-pop to a large, appreciative audience, and that distinctive soaring voice at the heart of every song.

One of the boys

In early publicity shots Brenda was just one of the boys, a member of the band, but as she blossomed into a solo artist the poses became more confident, the smile cheeky but also enigmatic.

There was little trace of that confidence now as she wandered around backstage, holding the coat tightly around herself as if preventing something vital from escaping. By my calculations she was barely into her 30s but she looked much older, worn down by her own hectic lifestyle.

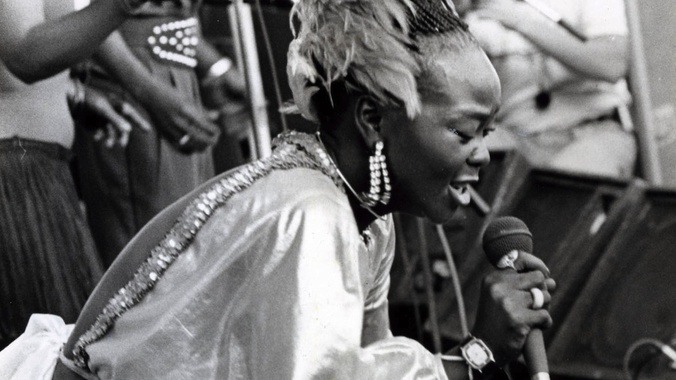

I was chatting to Mango Groove’s Claire Johnston when a crescendo of cheers from the crowd almost drowned out our conversation. I turned and there was Brenda centre-stage, singing her heart out, that voice pure and strong as it sailed out to all corners of the square.

In my memory’s eye she was wearing a white hot pants suit, but in truth I cannot be sure. What I do remember vividly is the crowd’s reaction to her presence. Every other act had been greeted with enthusiastic applause, but this was fervent adoration bordering on hysteria.

For full story see Mail & Guardian