Omar Badsha’s photographs, on show at a retrospective exhibition in Cape Town, reveal an artist determined to show the humanity of his subjects, writes Bongani Kona.

It’s early winter in Cape Town, cold and gray, when I take the 1044 train from Newlands station on a Saturday afternoon to meet the photographer Omar Badsha at his house in Woodstock. I sit in the half-empty carriage and page through one of his first photographic essays, Imijondolo: A photographic essay on forced removals in South Africa (1985).

Despite the grim subject matter of the work – the impending forced removal of a community of quarter of a million people living in the Inanda district, a shack settlement 30km northwest of Durban’s city centre – Badsha’s collection of black-and-white photographs eschews spectacle in favour of the everyday. Seedtime, a retrospective of his work on at the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town until August 2, is testament to this.

In one photograph, for example, a primary schoolteacher in her mid-50s is seen leaning against a wooden desk, pen in hand. Behind her is a throng of curious young learners. That the school is impoverished is easy to surmise from the children’s bare feet and the absence of any of the usual paraphernalia associated with well-functioning schools – desks, chairs, etcetera. But your eyes are pulled towards the soft face of the teacher, her lips arched in a half-smile. It’s her strength and resilience (not victimhood) that Badsha wants you to see.

I disembark from the train at Woodstock station. Years ago this was a working-class neighbourhood, not too dissimilar to the web of inner-city streets in Durban where Badsha grew up, the Imperial Ghetto as he called it. Now Woodstock is in the spasms of gentrification: the landscape is caught between a past on the threshold of vanishing and a future that is not yet realised.

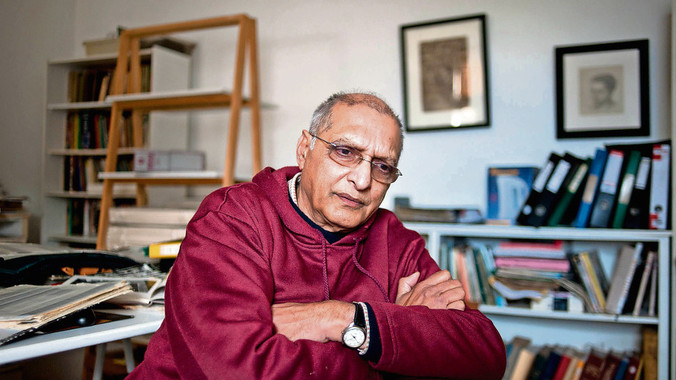

Badsha is a tall man, bespectacled, with thin gray hair. When he talks, he moves his arms the way a lecturer or a clergyman might to emphasise his point. Another thing about Badsha is that he almost never uses “I” even when talking about himself. He uses “you” – placing the collective above the individual. Indeed, listening to Badsha speak it’s hard to disentangle his own life story from the larger, collective story of the resistance to apartheid.

For the interview by Bonagni Kona with Omar Badsha, visit the Mail & Guardian

EXHIBITION: Seedtime, a retrospective of the work of Omar Badsha is on show at the Iziko South African National Gallery, Government Avenue, Company’s Garden, Cape Town until 2 August, 2015.