Original works by ‘the greatest copperplate technician’, Rembrandt, are being shown on a scale not seen in South Africa before, writes Lucinda Jolly.

Examples of Rembrandt’s etchings have previously been shown in South Africa, but never on the scale of the present exhibition, Rembrandt in South Africa. Drawn from at least seven private and public collections, the exhibition is made up of more than 100 etchings and numerous paintings ascribed to his “school”. Although South Africa has a number of paintings by artists in the style of Rembrandt, there are no unquestioned originals.

Curator Hayden Proud pointed out that there have been two narrow misses to procure the real deal. One involved the mining magnate and philanthropist, Sir Max Michaelis, the donor of Iziko’s Michaelis Collection. Proud explained that “the original intention was to include two key works, one by Rembrandt and one by his contemporary, Frans Hals”. These Dutch masterpieces are some of the paintings that make up the gift from Michaelis to South Africa, shortly after it became a Union in 1910.

He hoped to gain a title with this gift. Encouraged by his adviser, Sir Hugh Lane, Michaelis bought what was then known as the Demidoff Rembrandt, also titled Portrait of a Young Woman with a Glove. Before it left for Cape Town the painting – which had been authenticated by the “much-feared” German expert, Wilhelm van Bode – was showcased in London where it was rejected by critics and experts for being inauthentic. Outraged, Michaelis demanded his money back from Lane and with the proceeds bought works by 22 lesser-known artists which make up the Michaelis Collection.

The second near miss concerns the painting included in this current exhibition, The Taxidermist, which has recently been beautifully restored. As Proud indicated, Rembrandt’s students often copied him. If Rembrandt thought the painting was of a satisfactory standard he would sign the painting, endorsing it as his own. Authorship in those times was a looser affair. The Taxidermist was sent to the Netherlands in 1931 for further scrutiny after two researchers pronounced its authenticity. It turned out not to be an original, but one of three copies. The whereabouts of the original remains unknown.

The greatest copperplate technician

Etching was developed during the late Renaissance as a response to the growing demand for images from an increasingly literate middle class. The technique was known for its linear draughtsmanlike quality but the sheer innovativeness of the self- taught Rembrandt, who started etching in his late teens, pushed the edge of the technique’s envelope. For Rembrandt etching was a break from the incessant demands of painting. It was through this more accessible medium that his fame spread, rather than his paintings.

Rembrandt, “the greatest copperplate technician”, may have been forgotten for 200 years, then French Realists resuscitated him for his refusal, like them, to balk at the ordinary and the ugly in contemporary life. “Rembrandt’s Realism,” Proud reminds us, “almost led to his demise.” For such faithfulness to life was frowned upon by the Classicists of the time, who were obsessed with an ideal of beauty. Rembrandt’s deeply dimpled, wide-thighed, low-bellied nude women and potato-faced men, a dog taking a dump or a man urinating just wouldn’t do. Nor would his lack of concern for proportion in the service of expression.

But what is it in Rembrandt’s work that continues to intrigue viewers? Is it simply the monetary value of an old master with a long pedigree? And why should South Africans take any notice of another long-dead European artist of the same nationality of those who colonised them? Perhaps the answer lies in the artist’s understanding and rendering of the human condition in his etchings and paintings. Considered to be “a man of the people”, Rembrandt’s ability to find the theatrical in the mundane and make the ordinary extraordinary puts him in the same company as Goya.

A “typographer of the human face”

Whether beggars, quacks, pancake makers, saints or aristocrats, all Rembrandt’s subjects receive his clear-eyed, sharp observation tempered by compassion. To be seen in our totality with an unconditional empathic eye regardless of culture, gender or class is to be truly received and this resonates with a deep human longing. Described as a “typographer of the human face”, Rembrandt applied the same approach to his self-portraits, of which there are so many that he is regarded as the pioneer of self-portraits.

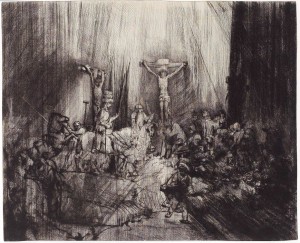

Rembrandt’s acute observation, paired with a profound range of mark-making, from the wispiest line to the densest of crosshatchings and segues of open spaces, made him one of the greatest artists of all time. His sense of the dramatic in the ordinary is fuelled by the intense play of light and dark of “chiaroscuro” – one of the hallmarks of the Baroque style of the 17th century. The current exhibition has been thematically grouped around the artist’s worn mother, who gave birth to 10 children, self–portraits, his wife Saskia and scenes from the Bible.

Rembrandt was a devout Christian and returned to the Bible throughout his life for examples of the human condition. Look out for the intensely powerful and late version Three Crosses from the Johannesburg Art Gallery, which Proud points out is “a great rarity”. One of the intriguing aspects of the collections that make up this exhibition is that the viewer sees the same etchings in many “states”, and how prints from the same etching plate can differ quite substantially according to how the printer has interpreted them.

Show Rembrandt Your World

In the Rembrandt spirit of things, there is a fun project called “Show Rembrandt Your World” generated by Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, one of the oldest art museums in the world. It’s rather like garden gnomes that are stolen and taken around the world, sending postcards home as they go. In place of a gnome is a framed, exact scale copy of a Rembrandt self-portrait that can be photographed in unusual situations.

Participants are encouraged to upload the photograph to Twitter, Facebook or Instagram using the hash tag #MyRembrandt. Already one of the copies has left Earth to make an interstellar stopover on the International Space Station. One of the seven portrait copies is on show at the Iziko Old Town House. Be sure to make use of the magnifying glasses on hire to examine the prints closely and be astonished by Rembrandt’s virtuosity and perspicaciousness.

Rembrandt in South Africa is on at the Iziko Old Town House until March 28 2015. Call 021 481 3933

via Mail & Guardian